One of my greatest frineds and triathlon training partners is a US Navy Dr. -- Andy Baldwin.

One of my greatest frineds and triathlon training partners is a US Navy Dr. -- Andy Baldwin.We've been on many triathlon adventures around the world, and he'll be on the starting line at Ironman Canada. For the past month, he was assigned to a very special mission.

He sent me a copy of his journal and some photos. I've published them below in their unedited form.

So much of the world can run, bike and swim for pleasure - and so much of the world is running simply from hunger and without access to the most basic human needs.

Here is his story...

-Mitch

A Doctor’s Adventure in Laos

My name is LT Andrew Baldwin, M.D. and I am the Diving Medical Officer for Mobile Diving and Salvage Unit ONE in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Earlier this year I was offered a once in a lifetime opportunity- a chance to go into the heart of Southeast Asia as a medical humanitarian and treat the sick and injured. I was asked to serve as group surgeon for a team of fifty military personnel headed for a one-month recovery mission in Laos attempting to find the remains of U.S. POW/MIAs from the Vietnam War. The Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC) is a powerfully funded Army-led organization that deploys numerous recovery missions to remote locations of the world each year. My role would be to take care of the medical needs of my team, and also to visit the remote villages where my teammates were working to treat Lao villagers in need of medical attention. What I would see and experience- disease and poverty coupled with courage and the will to survive- would change my life forever. Here are some stories from my adventure.

Running with Cows and Living with Bugs

5/1/06

After a successful flight on a huge Air Force C-17 from Hawaii to Thailand, and a hop on a C-130 to Pakse, Laos, we all passed through the rigid communist Laotian gates and in effect took a step back in time. Laos has just recently begun to loosen its policy restricting tourism and acceptance of foreign aid. But who can blame them? A little over thirty years ago we were secretly bombing their countryside for years during the Vietnam conflict in an attempt to prevent the communist Pathet Lao group from taking over. We bombed the Ho Chi Minh trail for over 9 years and failed in our intent. From an aerial view the Lao land appears like a vast maze of bomb craters. Thousands of bombs, mines, and other unexploded ordnance are still littered all over the country. Hundreds of Lao people (including many children), are killed each year as a result of our “hidden war in Laos.”

We arrived around midday after a long helicopter flight to our base camp in the small town of Taoy. It was a sweltering day, and I was instantly drenched in my long pants and collared shirt. I was shown to my tent where I would be living for the next month, and upon entering realized how rugged we would be living. The inside of the tent was full of huge red ants. I asked one of the Lao officials if the ants bite. He replied “sometimes, but it only hurts a little bit. Welcome to Laos!”

We arrived around midday after a long helicopter flight to our base camp in the small town of Taoy. It was a sweltering day, and I was instantly drenched in my long pants and collared shirt. I was shown to my tent where I would be living for the next month, and upon entering realized how rugged we would be living. The inside of the tent was full of huge red ants. I asked one of the Lao officials if the ants bite. He replied “sometimes, but it only hurts a little bit. Welcome to Laos!”I decided to put on my running shoes and go for a jog to explore. Running outside the base camp perimeter required a Lao escort, so I convinced a young kid (barefoot and smoking) to come along with me. We ran out the dirt road, through town, and soon had a few more runners join us. The only problem was they weren’t people. They were animals. We had pigs (and piglets) running after us for a while, then some chickens, and finally on the way back a herd of cattle charged behind us. I flinched upon their charge, but my barefooted buddy reassured me that things were ok. We arrived safely back at base camp, and I proceeded to the shower stalls for my first dirty shower. Imagine muddy, silty water (mixed with sodium hypochlorite) from a river coming out of the shower spout. All I have to say is thank goodness it rained sometimes.

Helicopter Rides and Doling out Medicine

5/5/06

This was my first MEDCAP site and not knowing fully what to expect I brought along an assortment of common medications, vitamins, toothbrushes, and medical/surgical supplies. We flew over in one of the smaller “Squirrel” helicopters with the Kiwi named Angus as our pilot. With some gentle nudging from Sergeant Baldeagle, Angus put the helo through some rolls and a stall maneuver that made our stomachs feel like we were on a rollercoaster. It was tons of fun. Unfortunately the Lao official did not think likewise and quickly put an end to our festivities. The personnel of Recovery Team One had constructed a makeshift medical clinic out of bamboo and black netting in a shady spot in preparation for my site visit. After finding some buckets to flip over and sit on, and some boxes to use as an examination table, the clinic day began. I had decided that every villager was to get a toothbrush and a bottle of multivitamins. Not thinking that we would have enough, the Lao official suggested that we not give these out. I vehemently overruled him, and proceeded as planned. This village of Laotians were “Lao Thien” which in Lao means mountain people.

This was my first MEDCAP site and not knowing fully what to expect I brought along an assortment of common medications, vitamins, toothbrushes, and medical/surgical supplies. We flew over in one of the smaller “Squirrel” helicopters with the Kiwi named Angus as our pilot. With some gentle nudging from Sergeant Baldeagle, Angus put the helo through some rolls and a stall maneuver that made our stomachs feel like we were on a rollercoaster. It was tons of fun. Unfortunately the Lao official did not think likewise and quickly put an end to our festivities. The personnel of Recovery Team One had constructed a makeshift medical clinic out of bamboo and black netting in a shady spot in preparation for my site visit. After finding some buckets to flip over and sit on, and some boxes to use as an examination table, the clinic day began. I had decided that every villager was to get a toothbrush and a bottle of multivitamins. Not thinking that we would have enough, the Lao official suggested that we not give these out. I vehemently overruled him, and proceeded as planned. This village of Laotians were “Lao Thien” which in Lao means mountain people. The Lao Thien are thought to be descendents of the ancient Kmer tribes from the south. They are of very small stature, dark skinned, lack the Asian features of other Laotians, and speak a different dialect (this tribe spoke “Brew”). We saw a steady stream of patients through the morning hours, with the males preceding the females. The patients’ small stature, malnutrition, poor dentition, and lack of hygiene was evident. Some appeared much older than their actual age (one woman whom the official and I was sure was in her thirties turned out to be just 15!). The most common complaints were toothache, rash, gastritis, headache, dizziness, and low back pain. For pain I gave Tylenol and Motrin, for abdominal discomfort I gave an assortment of Pepto-Bismol, TUMS, and Ranitidine, and for rash I gave out Clotrimazole ointment if it looked fungal, Lindane lotion for scabies, and Hydrocortisone and Benadryl for what looked like heat rash or dermatitis. I encouraged them to drink plenty of water with the pills in order to help alleviate their dehydrated status. Other problems I dealt with were two patients with conjunctivitis, three patients with worms, and one male patient with subjective malaria. The day ended having successfully used most of my medicines, and given away all of my vitamins and toothbrushes. In total I saw 63 patients this day.

The Lao Thien are thought to be descendents of the ancient Kmer tribes from the south. They are of very small stature, dark skinned, lack the Asian features of other Laotians, and speak a different dialect (this tribe spoke “Brew”). We saw a steady stream of patients through the morning hours, with the males preceding the females. The patients’ small stature, malnutrition, poor dentition, and lack of hygiene was evident. Some appeared much older than their actual age (one woman whom the official and I was sure was in her thirties turned out to be just 15!). The most common complaints were toothache, rash, gastritis, headache, dizziness, and low back pain. For pain I gave Tylenol and Motrin, for abdominal discomfort I gave an assortment of Pepto-Bismol, TUMS, and Ranitidine, and for rash I gave out Clotrimazole ointment if it looked fungal, Lindane lotion for scabies, and Hydrocortisone and Benadryl for what looked like heat rash or dermatitis. I encouraged them to drink plenty of water with the pills in order to help alleviate their dehydrated status. Other problems I dealt with were two patients with conjunctivitis, three patients with worms, and one male patient with subjective malaria. The day ended having successfully used most of my medicines, and given away all of my vitamins and toothbrushes. In total I saw 63 patients this day.Stepping Foot into Vietnam

5/10/06

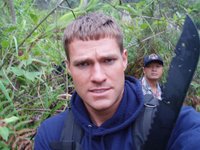

I had the day off from my medical duties and was asked if I would like to do some manual labor. One of the team needed some help in cutting a new helicopter landing zone closer to the plane crash site near the Vietnam Border. The pilot had failed to clear the Vietnam/Laos border ridgeline in 1969 and crashed into a very steep mountainside. We took a large Russian MI-17 helicopter to a clearing approximately 2k from the crash site. It was fairly overcast and cool morning, but nevertheless a spectacular ride up into the mountains. HMC Mabile and myself hiked through a recently cut trail to the proposed new LZ for the Squirrel helicopter. We carried our rucksacks and two chainsaws each along the ridgeline trail gazing at the valley of Vietnam below. We stopped for a quick picture straddling the border with our chainsaws held high. Upon reaching the site, I carefully walked down the steep mountainside to view the wreckage and work that had been done thus far. We visualized a casing for the rocket of a missile from the airplane as well as its engine block. There were about 25 Lao Thien (mountain tribal Laotians) there for labor and they had already built up forts under the tree canopy out of bamboo. I joined Chief Mabile back up at the proposed area for clearing and we got to work cutting down trees and clearing brush. I’ve never really used a chainsaw before, but I learned how to handle it well today. It provides quite the workout. I was sweating and fighting those trees all morning. The Lao workers were beating me in chopping down trees using their machetes! We broke for lunch around noon and I stumbled down the hill covered in wood chips and my clothes soaked with sweat and dirt. The Lao chief invited me and the other officers to their bamboo hut to eat with them. We enjoyed some of the best beef and pork I think I’ve ever had. We consumed it in the customary Lao style with balls of sticky rice, hot pepper sauce, and vegetables. I handed out some raisins and some canned pears, which the Lao people dubiously sampled after a little while. The afternoon sun was beating down in the clearing that we had created. We continued to clear trees and cut the stumps down to as low as possible, in order that the helicopter could make a safe landing. One area was teeming with fire ants and after fighting them off of my trousers, HMC Mabile and I quickly introduced them to gasoline and a match. It was quite fun. After some more clearing we had ourselves another surprise, as a huge tarantula came scrambling out of a tree. A Lao border guard shouldered his AK-47 rifle, and picked the tarantula up like it was no big deal. We were able to take some up close and personal photographs of the wiggling creature. The thunderclouds rolled in around 1500 and signaled our time to get out of their quick. We gathered our chainsaws and rucksacks up and headed up to the ridgeline trail and did double time in getting back to the helicopters. I had the opportunity to ride back in the smaller helicopter with the anthropologist, and team captain. They thanked me for my help out there, away from my doctor duties. The ride back was incredible navigating around thunderhead clouds and we even saw some magnificent waterfalls on the way. We landed safely at base camp and after showering up I had some time to reflect on the day and write this piece.

I had the day off from my medical duties and was asked if I would like to do some manual labor. One of the team needed some help in cutting a new helicopter landing zone closer to the plane crash site near the Vietnam Border. The pilot had failed to clear the Vietnam/Laos border ridgeline in 1969 and crashed into a very steep mountainside. We took a large Russian MI-17 helicopter to a clearing approximately 2k from the crash site. It was fairly overcast and cool morning, but nevertheless a spectacular ride up into the mountains. HMC Mabile and myself hiked through a recently cut trail to the proposed new LZ for the Squirrel helicopter. We carried our rucksacks and two chainsaws each along the ridgeline trail gazing at the valley of Vietnam below. We stopped for a quick picture straddling the border with our chainsaws held high. Upon reaching the site, I carefully walked down the steep mountainside to view the wreckage and work that had been done thus far. We visualized a casing for the rocket of a missile from the airplane as well as its engine block. There were about 25 Lao Thien (mountain tribal Laotians) there for labor and they had already built up forts under the tree canopy out of bamboo. I joined Chief Mabile back up at the proposed area for clearing and we got to work cutting down trees and clearing brush. I’ve never really used a chainsaw before, but I learned how to handle it well today. It provides quite the workout. I was sweating and fighting those trees all morning. The Lao workers were beating me in chopping down trees using their machetes! We broke for lunch around noon and I stumbled down the hill covered in wood chips and my clothes soaked with sweat and dirt. The Lao chief invited me and the other officers to their bamboo hut to eat with them. We enjoyed some of the best beef and pork I think I’ve ever had. We consumed it in the customary Lao style with balls of sticky rice, hot pepper sauce, and vegetables. I handed out some raisins and some canned pears, which the Lao people dubiously sampled after a little while. The afternoon sun was beating down in the clearing that we had created. We continued to clear trees and cut the stumps down to as low as possible, in order that the helicopter could make a safe landing. One area was teeming with fire ants and after fighting them off of my trousers, HMC Mabile and I quickly introduced them to gasoline and a match. It was quite fun. After some more clearing we had ourselves another surprise, as a huge tarantula came scrambling out of a tree. A Lao border guard shouldered his AK-47 rifle, and picked the tarantula up like it was no big deal. We were able to take some up close and personal photographs of the wiggling creature. The thunderclouds rolled in around 1500 and signaled our time to get out of their quick. We gathered our chainsaws and rucksacks up and headed up to the ridgeline trail and did double time in getting back to the helicopters. I had the opportunity to ride back in the smaller helicopter with the anthropologist, and team captain. They thanked me for my help out there, away from my doctor duties. The ride back was incredible navigating around thunderhead clouds and we even saw some magnificent waterfalls on the way. We landed safely at base camp and after showering up I had some time to reflect on the day and write this piece.Worms, and hardworking women

5/12/06

There are numerous parasitic diseases that afflict people in Southeast Asia. These are infectious diseases that I learned about in medical school, but have never seen in the United States. In my evaluation of the Lao thus far I have seen numerous cases of lice, scabies, worms(ascaris) and liver flukes (amoebas). Worms and flukes are some primary causes of liver failure and gastrointestinal distress and bleeding. Liver failure is currently one of the major causes of death in Laos. The main route of worm entry is through the foot (cuts /walking barefoot), and through fecal-oral transmission (mostly via food).

Amoebas are water-borne and found in the rivers, and lakes. You would rarely see such conditions in modern countries like ours, but here it is endemic. With our high potency drugs the cure is so easy. I’ve been giving out two doses of Albendazole to many people, which is all it takes to get rid of the worms. It’s the future prevention of getting it again that is the problem. Preventative medicine is largely nonexistent in this third-world nation. Little thought is put into the future. It is all about getting food in their stomach, and taking care of their immediate problems. It proved to be very frustrating to me when I gave them instructions on how to care for their health. They just don’t think that way.

Another observation that I have made is that the women do mostly all of the work, while the men lie around, smoke tobacco, and enjoy fresh meat, vegetables and rice, and then nap in the shade. The women have no such luxury. Their lunch consists of just rice (the men eat all the meat) and they are out laboring away under the scorching sun all day. The lack of protein/calcium intake is evident in their short stature, weathered skin, poor dentition and overall poor health as compared to the men. It is quite sad. The women tend to look older than their actual age, while the men look younger than they actually are. I made a point to give out as many multivitamins to the women as possible.

Another observation that I have made is that the women do mostly all of the work, while the men lie around, smoke tobacco, and enjoy fresh meat, vegetables and rice, and then nap in the shade. The women have no such luxury. Their lunch consists of just rice (the men eat all the meat) and they are out laboring away under the scorching sun all day. The lack of protein/calcium intake is evident in their short stature, weathered skin, poor dentition and overall poor health as compared to the men. It is quite sad. The women tend to look older than their actual age, while the men look younger than they actually are. I made a point to give out as many multivitamins to the women as possible.Into the Bush on an Investigative Mission

5/15/06

Situation:

1969– Southeastern Laos

Ambush and killing of five Special Forces U.S. Army personnel on mountain ridge by the VietCong. Bodies not recovered, site of attack in question.

1979 – Laotian farmer comes across the bodies on the ridge with his herd of cows. One of his cows is blown up by either a piece of unexploded ordnance or mine. The bodies are thought to be bad luck and are avoided by the locals.

37 years later…..the exact location of the site remains in question.

Yesterday I was asked by the RT-1 Team Leader, Captain George Eyster whether I would be willing to be a part of an investigative mission into the jungle along with himself, Sergeant Baldeagle and a Lao official. He explained that they were in search of “Site 1522” which had eluded many teams in the past due to it’s location at high altitude on a steep ridge, and that a full team insertion had not been possible because there was not a good landing zone for a helicopter. He explained that they wanted to jump in off a helo, hike through the jungle to the ridge, identify the site, cut a landing zone on the ridge, and get extracted. There was a significant risk of a casualty with the helicopter drop off and possible UXO in the area, so they needed a medic along, and someone who was fit and could carry the chainsaw and hike for quite some distance in thick brush. I readily agreed.

We awoke this morning to howling winds and chilly temperatures. It was so cold I had to break out my sweatshirt and thought it amazing that just two days ago I had been sweltering hot and wishing I could take my shirt off. There was talk of whether the cloud cover was too low and the winds too strong to fly the helicopters today. We prepared for the mission regardless and decided to see if the skies would clear. I made sure to pack enough food and water to spend the night if we got stuck out there. For medical supplies, I packed a tourniquet, IV fluids, blood clotting agents, and battle dressings.

These were the basics needed for treating any large blast injury or trauma in the field. We were each issued walkie-talkies so that we would have good communication ability on the mountain. Captain Eyster would carry the map and GPS unit, his Ranger bag, rope and a machete, Sergeant Baldeagle would carry the EOD metal detector, his Ranger bag, and a hatchet, and I would carry my medical bag, a machete, and the chainsaw. We waited patiently, and by 0830 we were airborne with Andy the pilot and two Lao officials. We headed eastward into the mountains climbing to near 4000 feet through the dense clouds of the morning. Halfway there we spotted the larger Russian MI-17 helicopter heading the opposite direction back to Base Camp. They had been turned around due to thunderstorms and bad weather. We decided to press on and finally reached the designated mountain range. Captain Eyster was determined to get a good orientation of the ridge from the air and attempt to correlate the GPS coordinates and his map locations. I snapped some photographs for later comparison with the others. Andy the Pilot took us all over the mountain airspace and we identified possible drop off sites. We found an area of tall grass in a valley, two mountain peaks away from the designated ridgeline, and that’s what we decided to go for. We then went back to the local village to prepare for our jump. The plan was that Andy would hover 5-6 feet above the ground and we would jump out one by one, throwing our bags and equipment before us, and unfortunately (so we thought at the time) we had to take a Lao official with us. We all did a radio check and decided on a primary rendezvous point at a spot below the ridge where we cut the landing zone, and a backup rendezvous point as the top of the ridgeline. Andy would be at the primary at 1300 and the secondary at 1315 if we failed to show at the first. We reached the drop zone, and Andy began his hover. As we opened the door, the adrenaline rush hit, the rotor blades were spinning overhead, the intense wind from the rotor wash, blades of grass swirling every which way below us. We jumped out one after the other including the Lao official (in his nice shirt and dress shoes). I hit the ground and rolled, recovered and was able to snap a picture of the exiting helicopter from below. Everyone had made the jump safely, and now Captain Eyster led the way with his machete as we tried to cut our way toward the tree line through this massive grass which was twice as tall as any of us.

The Lao official trailed nimbly, obviously comfortable in his native land. It was slow going and after about 45 minutes of hacking and stumbling we finally made it to the trees where things opened up a bit. We had forgotten to wear gloves, and suffered dearly from all of the thorns and sharp grass which tore up our hands. Once we reached the tree line I made all of the guys stop and hydrate and I took out some of my Kerlex gauze and wrapped one of my fingers which had a pretty deep slice in it and was bleeding profusely. A little tourniquet action and things were all good. We pressed on for about another kilometer cutting across the mountain slope, and then stopped so Captain Eyster could take a GPS reading. We had made ok time and were about 500 meters down the mountain from the supposed site location, and about 200 meters up from the prospective landing zone that we were going to cut. Captain Eyster made the decision to abandon our proposed LZ and instead head for the site and the ridgeline. It would be too steep and too far from the site to the have the LZ in the previously proposed location. We turned uphill and I soon found myself leading the way through the brush, with my chainsaw in tow. It was hard going and very steep and the lack of fitness began to show in some members of our group. I pressed on and tried to cut the best route through the jungle. As I made my way uphill I was practicing good circumspection looking all around for any sign of manmade material, ordnance, or mines. Unfortunately Captain Eyster informed us, we had lost all of our satellite contacts on the GPS machine due to the dense foliage overhead so we were using our compass and approximating how far we had gone. It took us about an hour until we reached the top of the ridge. We stopped to hydrate and catch our breath. The trees were thicker than ever, and our hopes of cutting an LZ up here were dashed. We had reached quite an elevation and now were consumed by the clouds, and as we rested and felt our sweaty brows, we actually realized how cold it was. We were 3 freezing U.S. Gorillas in the Mist, and a Lao official. We had to keep moving. Captain Eyster consulted the map as the GPS still was not picking up a signal, and we decided to walk along the ridgeline to an even higher altitude to try and find a GPS signal. Sergeant Baldeagle led the way, and as the brush and foliage got even denser, I could sense his frustration and I too found myself getting frustrated and wondering how the hell we were going to get out of this mess. I put my hood up and told myself to keep going. We continued through the thorny brush, vines and triple canopy rainforest.

After what seemed like an eternity I heard Captain Eyster yell, “I have one satellite reading on the GPS!” We walked a little further. “Two satellites, Three!” He could now triangulate our position, and as luck would have it we were almost dead-on with our rudimentary navigation. We were about 20 meters from the site coordinates and had emerged into a clearing on the ridge which we finally decided would have to do as our helicopter landing zone. Luckily, our radios also functioned at our current location and we were able to contact Andy the Pilot and inform him of our change of plans and request some more time for the clearing of the landing zone. It was going to take some serious manpower as there were only three of us armed with just a hatchet, a machete, and a chainsaw. Luckily the Lao official was keen on helping us as well, and he whipped out his custom made machete. We set to work immediately without time to spare. Baldeagle began falling the large trees with the chainsaw as Captain Easter and I cleared smaller brush and bamboo. The Lao official (still in his collared shirt and dress shoes and looking largely unscathed) began falling trees with his machete like he was Paul Bunyan. We were relieved to have him along. Cutting a makeshift landing zone took quite some time, and an amazing amount of energy. The ground was not very level, and there were tree stumps, and huge pine trees to contend with. We prayed that Andy would be able to set the helicopter down in this site. Otherwise we would be spending the night, or would have to hike back down through the brush to the distant river bed. As it got further and further into the afternoon, the landing zone came into being and we decided to give Andy a radio call and give it a shot. Andy was on his way, and we prepared for the extraction. He maneuvered onto the site perfectly avoiding the trees, we loaded our bags and our filthy selves into the helicopter and prayed we would make it out of the dense foliage safely. Andy made the sign of the cross, and lifted off and before we knew it we were airborne and out of that hell zone of a jungle. Mission accomplished! We had correlated the GPS coordinates and location of the site, cut an LZ near the site on the ridgeline, and made it out of their safely. After some cleaning up and licking of our wounds back at base camp, we were ready for some beers, and some rest. There was much more work to be done yet in finding our fallen comrades from 1969.

My Favorite Village

5/22/06

Today was my third visit to Site 0947. Out of all of the four sites, 0947 has the friendliest and most outgoing workers. The workers and children would always have a smile on their face, and would come out in droves when the Dr. Baldwin was in town. The first time I made a medical visit there I saw over 90 people (mostly children), the second time over 110 and today I wasn’t sure what to expect. I packed my medical box to the brim with vitamins, toothbrushes, and medications. I was really looking forward to seeing if the patients I had evaluated and treated in weeks past had made any improvement with my treatment. For me, being able to treat those in need and then witnessing improvement in their health is the most rewarding part of being a doctor. I was able to experience it this day with many of my Lao patients. One child who could not even open his eyes because his eyelids were infected, swollen, and pus filled just two weeks ago, was completely healed, smiling, and playing with the other children. He was no longer an outcast. Another child who had fallen ill with malaria was back on his feet again, fever free, after a few doses of the expensive wonder drug Fansidar. I had treated a teenage girl a week prior who came to me with a large downward gash in her left heel which left her Achilles tendon exposed. She had walked several kilometers, without shoes to see me, and her wound was filled with dirt, grime and bacteria. I irrigated it thoroughly and stitched it up and gave her some antibiotics. She returned to me today, infection free, and the wound healing well. She was almost ready to get her stitches out! The beauty about treating infections in the 3rd world is that there is virtually no antibiotic resistance. Basic penicillin will kill just about anything. If only it were still that way in the States….

Today was my third visit to Site 0947. Out of all of the four sites, 0947 has the friendliest and most outgoing workers. The workers and children would always have a smile on their face, and would come out in droves when the Dr. Baldwin was in town. The first time I made a medical visit there I saw over 90 people (mostly children), the second time over 110 and today I wasn’t sure what to expect. I packed my medical box to the brim with vitamins, toothbrushes, and medications. I was really looking forward to seeing if the patients I had evaluated and treated in weeks past had made any improvement with my treatment. For me, being able to treat those in need and then witnessing improvement in their health is the most rewarding part of being a doctor. I was able to experience it this day with many of my Lao patients. One child who could not even open his eyes because his eyelids were infected, swollen, and pus filled just two weeks ago, was completely healed, smiling, and playing with the other children. He was no longer an outcast. Another child who had fallen ill with malaria was back on his feet again, fever free, after a few doses of the expensive wonder drug Fansidar. I had treated a teenage girl a week prior who came to me with a large downward gash in her left heel which left her Achilles tendon exposed. She had walked several kilometers, without shoes to see me, and her wound was filled with dirt, grime and bacteria. I irrigated it thoroughly and stitched it up and gave her some antibiotics. She returned to me today, infection free, and the wound healing well. She was almost ready to get her stitches out! The beauty about treating infections in the 3rd world is that there is virtually no antibiotic resistance. Basic penicillin will kill just about anything. If only it were still that way in the States….I saw many patients throughout the day with positive outcomes- rashes cured, ear infections gone, worms destroyed. It felt great. To top things off, at the end of the day the village chief told me through a translator how grateful the villagers were for all of my help. He appreciated all of the time I spent with his patients and said that I was the best doctor he had ever seen. Knowing that he probably hadn’t seen too many doctors in his day, I wasn’t quite sure how to take that. Nevertheless, I took it as a compliment. It was deeply rewarding.

Ambassador Comes to Town

5/25/06

The U.S. Ambassador to Laos paid a visit to the dig sites today, and also visited Taoy base camp and the town’s medical clinic. I accompanied her to the 1 year-old medical clinic. It was raining and there were leaks in the ceiling, chickens and pigs walking through the hallways, and babies crawling on the dirty floor. I just shook my head….. What a difference from U.S. hospitals. But this clinic was a godsend for the local people, most importantly for child birth. The current infant mortality rate in the mountain regions was exceeding 50%! Now, the word was getting around in the community that there was a local facility to go to which could provide obstetric and pediatric care. The clinic was averaging one birth a day, with only a 10% mortality rate. The Ambassador was quite impressed. U.S. money had been used to fund the construction of the clinic. But she was not as cheery about the birds in the hallways, with the current proximity of avian flu in Southeast Asia. The clinic was also in dire need of supplies, and medications. The Ambassador and I discussed these issues and others, such as hurdles in getting Laos better medical care, and the frustrations of living in a communist state.

A TRIATHLETE IN LAOS?

A TRIATHLETE IN LAOS?It took about a week in Laos until I started losing my mind. It wasn’t the rough living conditions that got to me. It wasn’t the bugs. It wasn’t the isolation. It wasn’t the dirty water we were showering with. It was the fact that I couldn’t work out and train in my normal routine. I am an avid Ironman triathlete who is used to working out two to three times per day. My psyche and my body depend on those daily workouts. But in the middle of the mountains in eastern Laos, there is not a pool right around the corner. And forget biking. There were no bikes in Laos that I observed, and even if there were, the tires would never hold up on that awful, rocky, muddy road. The good news is that I could run, but only between the hours of 1600 and 1800 and with mandatory accompaniment by three Lao officials. The “running law” was that one could run out 1 mile and then had to turn around.

My Lao “running guards” were a bit behind in the fitness category. Some of their lack of fitness could be contributed to other variables. I mean, they ran with cigarettes in their mouth and with shoes that appeared to have come from a bowling alley. They began to stage themselves along the 1 mile route, so that when one would tire, they would hand off duties to the next guy to try and keep up with me. I was so irritated that I couldn’t go farther out than one mile. My big question for the Lao was “where was I going to go?” It’s not like there was a big city nearby, or any place that I could cause any semblance of trouble. We were in the middle of nowhere, and I wasn’t allowed to run more than two miles. I tried once to “unknowingly” wander out for a run at 0500 hoping to avoid my escorts. I can’t tell you the sense of freedom that I felt as I began to stride down that dirt road alone, with the exception of an occasional cow or pig that would tag along. As I passed the one mile marker I felt a sense of relief. I was going to run as far as I wanted that morning…..or so I thought. Suddenly one of the Lao smoker runners emerged from the brush, and yelled out at me “Stop!” I pretended not to hear him. I mean for heavens sake, did he camp out and sleep at the 1 mile marker??? He yelled out again to stop. And it was at that time I gave in and stopped. “You got me pal,” I relented. There was no way around the situation.

When I was running back to base with my tail between my legs, I realized how convenient exercise is in the United States, and how many of us take that for granted. We have countless gyms and pools, tennis courts, bicycles, paved roads, and the freedom to run from coast to coast on a whim, if we wanted to. In Laos, for me, there was none of this. Many athletes use exercise to achieve a positive physical and mental state. They get into a routine and their psyche depends on it. The worst nightmare for many athletes is to get injured, because they are physically restrained from working out. For me in Laos I also felt restrained, injured in a way, and there was nothing I could do about it. I realized that I couldn’t fight it, and had to change my expectations, change my perspective and embrace the culture and situation I was in. Once that paradigm shift occurred things took on a life of their own. I allowed myself to relax and not worry about how many miles I had to run in a certain day. I played the Lao version of Bocci ball with the locals every evening, and occasionally we would have a pick-up game of soccer or I would teach them how to play horseshoes. By acknowledging the situation I was dealt, and changing my approach, I emerged from that month with some very close friendships with the locals that I would not have had otherwise. Lesson- in difficult situations, take a step back, look at the big picture, and realize that is ok to release yourself from the grips of that rigid training plan sometimes.

Turnover of Medications to the Local Medical Clinic

5/28/06

I did a successful turnover of all of my remaining medications and medical surgical supplies. The clinic doctor and head nurse expressed their deep felt appreciation for the U.S. aid and for my work in the villages there. As a token of their appreciation they presented me with a hand woven wicker basket used to carry sticky rice (the main staple of Laotian cuisine).

Conclusion

6/1/06

I had been living in virtual isolation for over a month now, and even the return to the small town of Savanakhet on the Mekong River in lowland Laos provided me with a bit of culture shock. Being able to check email, enjoy an ice cream, watch TV, and shower with clean water were all things that I had grown accustomed to not having.

I had a lot of time to reflect on my trip over the next few days, and it truly did feel like a trip back in time. I’ll never forget the way the villagers up in the mountains stared at me when I got out of the helicopter. Many of them had never seen a white person before, let alone a helicopter. It was like they saw me as a god. Most of them were not fully clothed, did not have shoes, and through their constant smiles you could see they were missing most of their teeth. Their main priority in life was to get enough food to survive, and pay homage to the spirits that they worshipped. Their attitudes were so positive, and their enthusiasm contagious. I kept trying to put myself in their minds and imagine how such positive energy could exist in a life of such poverty and simplicity. But the reality of it is that they don’t know any other world. They don’t share our 1st-world perspective- a mindset from a land filled with convenience and luxury, stress and selfishness, depression and complaints. Oh, if only we all could realize how good we really have it and how lucky we are.

I had a lot of time to reflect on my trip over the next few days, and it truly did feel like a trip back in time. I’ll never forget the way the villagers up in the mountains stared at me when I got out of the helicopter. Many of them had never seen a white person before, let alone a helicopter. It was like they saw me as a god. Most of them were not fully clothed, did not have shoes, and through their constant smiles you could see they were missing most of their teeth. Their main priority in life was to get enough food to survive, and pay homage to the spirits that they worshipped. Their attitudes were so positive, and their enthusiasm contagious. I kept trying to put myself in their minds and imagine how such positive energy could exist in a life of such poverty and simplicity. But the reality of it is that they don’t know any other world. They don’t share our 1st-world perspective- a mindset from a land filled with convenience and luxury, stress and selfishness, depression and complaints. Oh, if only we all could realize how good we really have it and how lucky we are.I treated a total of 611 Laotian patients during my humanitarian medical excursion to Laos. It was the most rewarding and eye-opening experience of my life.

For more articles and photos of Andy - click here to see this entire blog and scroll down.